As is well-known, every medieval castle was designed as a fortress of sorts. And why was that? Because there were constant skirmishes in that era, which ensured that even a petty disagreement could result in an attack. So, with that in mind, what do you think is the most vulnerable part of a medieval castle? It’s where the enemies can get at the easiest: the entrance.

Table of Contents

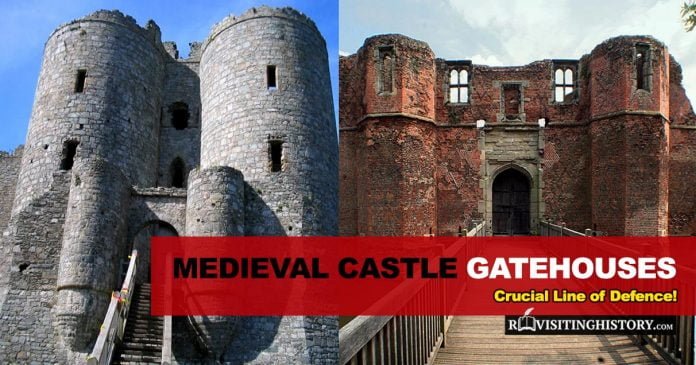

Thus starts the story of the medieval gatehouse, an architectural accessory that was specially designed to make sieges and attacks as difficult as possible. It’s basically a defensive structure that consisted of various traps, portcullises, and even murder holes to keep the enemy from getting inside.

Typically spanning 2 or 3 stories high, these gates weren’t just the first line of defense, they were also a symbol of might that set the architectural tone of the castle from the get-go. If you’re a connoisseur of medieval architecture, then you’ll certainly love all the information we’ve got on the gatehouse below. Let’s take a look:

Where exactly is the medieval gatehouse located?

Since the very etymology of the term “medieval gatehouse” contains the word “gate”, it suffices to say that it was designed for the entrance of the castle. Now, it’s important to understand that this was not just a typical medieval gate. The gatehouse was an entire defensive structure that consisted of a small, separate building with a passageway. Anytime an enemy planned a castle attack, they’d have to survive the gateway in order to get inside. If you’d like to learn about other defense systems most castles had, go ahead and read this article.

On a modern note, having a gate may seem like common sense. But back in the medieval era, it was quite a revolutionary idea. In fact, one of the very first documented medieval gates originated at Dover Castle in England circa the 11th century. Experts believe that gatehouses began to appear more and more after wooden castles started being replaced by stone ones.

What Were Common Parts of a Medieval Gatehouse?

Getting into the gatehouse required making it through quite a few difficult areas, starting with the approach. Flanking towers on either side of the gatehouse allowed to archers to keep sight of the enemy and fire accordingly. Sometimes, the path leading to the entrance would also be inclined or bending. Enemies would tire out and have trouble dragging their battering rams uphill.

Associated with moats, the drawbridge is one of the most iconic parts of a medieval gateway. It was hung over a defensive ditch or moat in times of peace (by the way, moat-and-bailey castles are Norman invention). But when it came to sieges, it was drawn back and the enemy had to think of innovative ways to bypass the moat/ditch in order to get inside. Dover Castle, however, has an interesting alternative to the moat/ditch pairing, where a deep pit is revealed only once the drawbridge has been raised.

Do you know that iron gateway that is lowered down in every period Hollywood movie whenever an enemy attacks the castle? It’s called a portcullis. It was installed at the front of the actual gate and acted as the first line of defense once an enemy attacked.

The earliest ones were usually made from sturdy oak wood, but later versions were pure iron for maximum impact. They did have the major setback of being extremely heavy. That is why wooden portcullises with metal coatings were more popular. These used to have pointy edges at the bottom in order to neatly fit into holes at the base of the gate … and to crush enemies as well.

Inside the Gatehouse

The horrors (for invaders) didn’t stop once they’d made it past the first portcullis. They still had quite a way to survive to get into the castle itself.

The actual gate itself in the medieval gatehouse was made from wood. It needed to be lightweight in order to be moved easily. However, gates were made to be as thick as possible in order to maximize their strength for siege situations. Often, the wood was enjoined/layered in a criss-cross pattern to make it harder to break down.

There were often two portcullises in the gatehouse, with a second one behind the wooden gate. Once the enemy entered the gate, both of these would be dropped in quick succession and the enemy would be instantly trapped. When that happened, the other traps were activated, which brings us to…

Murder Holes

Your typical medieval gate was made from heavy stone blocks and had some pretty nasty built-in traps, the worst of which were the “murder holes.” Now, these were actual holes that were built within the gatehouse passageway, used to drop heavy objects on top of any enemy stragglers that might have made it past the portcullis. Other than boulders, burning hot liquids like tar and boiling oil were also used to incapacitate the attackers.

Chapels

Since Christianity was the prevalent religion at the time, some medieval gatehouses also had built-in chapels so that it would provide some manner of godly protection if there was a siege. Alternatively, destroying the chapel could incur the anger of God on the enemy.

Explore Medieval Times Deeper or Continue Reading…

What are the two main parts of the gatehouse and what were they used for?

The main structure of the medieval gatehouse was designed for pure defense. However, over the years, it saw quite a dichotomy in its function develop. The entrance was the first and foremost part of the gate and was lined with adequate defensive systems to keep enemies at bay. The second part of the gatehouse became the extensive series of buildings that added to its might in a more symbolic way.

Since the gatehouse became an emblem of might, it wasn’t just used as an entrance anymore. Many began to boast of the castle’s grandiosity by hosting opulent rooms and apartments. The first floor was given over to the gatekeeper, but the upper floors were the penthouse suits of the medieval era. This is where some of the grandest visitors would stay.

When warfare became less of a threat in Britain (circa the last half of the medieval period), gatehouses began to become less defensive and more decorative. Now, they were a symbol of prestige: an icon of the master’s pedigree and place in society.

The gatehouse of Raglan Castle is one of the finest examples of this phenomenon. Flanked by two impressive towers on either side, the magnificence of this entrance cannot be denied, but when it came to actual defenses, it was quite moot. The gatehouse of Harlech Castle, on the other hand, was much more sophisticated. Its twin towers had two floors that overlooked a courtyard and the entrance had seven obstacles that made it very hard for the enemy to get inside.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How were gates opened in Medieval times?

While the main doors of the medieval gates were made of wood and attached to the jambs with hinges, the portcullises were actually raised and dropped with the help of old-school pulleys that were installed at the very top of the gatehouse. The concept was a bit like modern-day lifts, only there was actual manpower needed to pull the anchors so that the portcullis could be lifted.

How were medieval gates locked?

The wooden doors had a deadbolt lock while the portcullis would fit into the corresponding holes that were dug into the ground for its pointed base.

History itself is evidence enough that had it not been for the gatehouse, medieval castles would have been so much more vulnerable and so much less interesting … with a potential lack of murder holes and grand apartments. They weren’t just majestic and mighty, but some of the existing gatehouses today have seen major historic battles and survived to tell the tale. Moreover, they acted as a dam that kept the medieval keep–the beating residential heart of the castle–as secure as possible.

That said, this is everything that you need to know about medieval gatehouses, how they came to be, what they were used for, and what became of them in the end. We hope this comprehensive guide helps you understand this significant part of medieval architecture in a thorough way.